By Shikhar Aggarwal

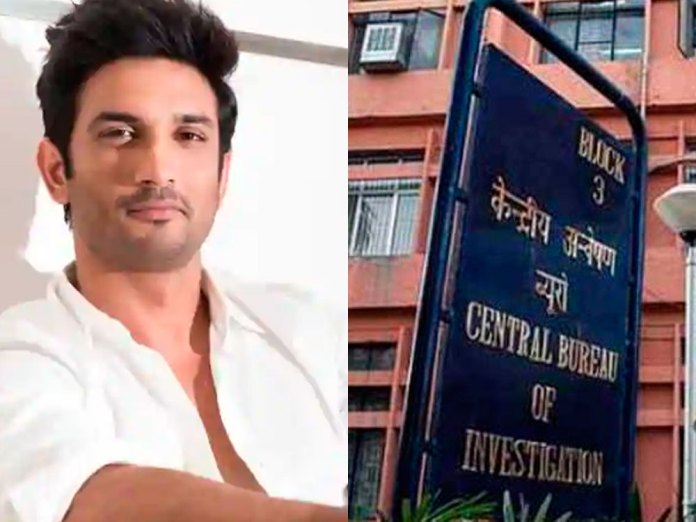

The recent Supreme Court judgment, transferring the probe into the unnatural death of actor Sushant Singh Rajput and the surrounding circumstances, to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), is being hailed as a victory for the public sentiment attached with the aftermath of his death. On the other hand, some believe that it may have set an incorrect precedent for the future. This article seeks to analyse the legal basis upon which a local investigation may be transferred to the CBI, what role the judiciary has in ordering such transfer, what the SC held in this case, along with exploring its possible legal implications.

Every offence is ordinarily inquired into and tried by a Court within whose local jurisdiction an offence is committed. Accordingly, Police departments are entrusted with the power of investigation over crimes, under the control of State Governments. However, there might be cases where an investigation may not be conducted properly and may cause serious prejudice.

However, an improper investigation in itself cannot be the sole reason behind an acquittal. The Supreme Court has urged courts not merely to pick lapses in the investigation, but also to consider constraints of police officers, the ill-equipped investigation machinery, and traditional apathy of respectable people in giving evidence.

That said, the Court may transfer an investigation to another agency only in rare and exceptional cases, when necessary to do justice and to instill public confidence in a ‘fair, honest and complete’ investigation conducted by State functionaries. In-State of W.B. v Committee for Protection of Democratic Rights, the SC held that powers under Articles 32 or 226 of the Constitution are not curtailed by Section 6 of the Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act, 1946, which requires a State’s consent for the transfer of investigation to the CBI.

Therefore, the CBI may be directed to investigate a cognizable offence within a State’s territory, if without its consent thenupon a Writ Petition. The Courts have an obligation to exercise such power with great caution. An order directing a CBI investigation may be passed only when the Court, after considering the material on record, concludes that it discloses a prima facie case for an investigation by the CBI or any similar agency.

Therefore, the investigation may be transferred to a central agency where: (a) high State officials may be involved in the commission of offences; (b) the accusation is against top officials of the investigating agency, who may influence the investigation; and (c) where the investigation is prima facie tainted or biased.

After actor Sushant Singh Rajput died by suicide at his residence in Mumbai in June, there have been various theories pertaining to his demise, including suspected murder, money laundering, and accusations of abetment to suicide by actress Rhea Chakraborty.

In July, the deceased’s father filed an FIR before the Bihar Police for offences under the IPC relating to criminal conspiracy, cheating, criminal intimidation, abetment of suicide, etc. This FIR was filed at time when the Mumbai Police had been investigating the cause of unnatural death under Section 174 CrPC.

The two Police departments ‘investigating the case’ had been embroiled in controversy, when officers from Patna had been quarantined upon their arrival in Mumbai, and allegations of politicisation had been exchanged. In the meantime, the Bihar Government decided to hand over the case to CBI, under Section 6 of the DSPE Act.

Accordingly, Chakraborty filed a Transfer Petition before the Supreme Court, stating that the incidents alleged in the FIR took place within the jurisdiction of Mumbai Police, and the FIR as received should have been forwarded. It was contended that the State of Bihar’s consent for the transfer to CBI was not lawful, for want of jurisdiction.

Adjudicating upon her plea and the overall question of jurisdiction, a Single Bench of Justice Hrishikesh Roy, relying on Lalita Kumari v State of U.P., held that Bihar Police was mandated to register the FIR in respect of the alleged cognizable offences. This could not be declined on mere ‘territorial grounds’. Additionally, Bihar Police was said to have properly exercised jurisdiction under Section 181(4) CrPC, which declares the place of trial in case of criminal misappropriation or breach of trust.

This was because the deceased’s father had a cause of action in respect of the said offence(s) since the money was to be eventually returned/accounted for in Patna, where the deceased’s family resided. On those lines, the Court declared that the Bihar government was competent to consent for transferring the investigation to the CBI, thereby validating the transfer and directing Mumbai Police to hand over case files and render necessary cooperation.

Interestingly, the Court did not find any prima facie evidence of any wrongdoing on the part of the Mumbai Police. The Court observed that its legitimacy had come under a cloud, considering “speculative public discourse which has hogged media limelight.” Further, the Court held that obstruction(s) caused to the Bihar Police team in Mumbai raised suspicions about the bona fides of their inquiry, necessitating transfer to an “independent agency not controlled by either of the two-state governments”.

Therefore, the Court aimed to uphold the credibility of the investigation, and to do so, it felt the need to specify the authority/agency which should conduct the investigation. Invoking plenary jurisdiction under Article 142 of the Constitution, to ensure public confidence in the investigation, the Bench empowered the CBI to investigate not only the cause of unnatural death but also any future cases pertaining to the surrounding circumstances, thereby bypassing Section 6 of the DSPE Act.

The Court did not explain how public confidence in an investigation may be shaken purely on the basis of speculations when there are no established wrongdoings on the part of an investigating department. Further, the SC permitted such transfers only upon a Writ Petition, which was not even filed in this case. Therefore, the legal basis upon which the Court transferred this case to the CBI, without the consent of the State of Maharashtra, stands on shaky grounds.

It may be argued that in this case, a reason for permitting the transfer of investigation may be the subject-matter of the operations pursued by the two departments, and the application of Section 6 is not warranted. The Mumbai Police was only pursuing a limited inquiry under Section 174 CrPC, which is distinct from a full-fledged “investigation” of an offence under Section 157, especially since it had not registered an FIR.

That said, this judgment has immense potential to become an erroneous precedent. There may be situations where every sensational case, based on conspiracy theories arisen from a media trial, would necessarily be referred to the CBI and not be inquired/ investigated into by the local Police. Ultimately this precedent may be (mis)used to circumvent the federal structure of our country and the concept of separation of powers.

Since no one party to a case is ever fully satisfied with the outcome of an investigation (which may not otherwise be tainted), they may file petitions requesting a transfer to the CBI. Accordingly, a State Government may be deprived of the power to refer matters to a central authority (through such non-consensual transfers), despite the lawful conduct of local agencies.

In this case, the SC rightly held that Bihar Police had jurisdiction under Section 181. However, in a future case, if this judgment is read to permit registration of complaint in other States (beyond Chapter XII of the CrPC), the law may inadvertently enable a person to choose investigating authorities, in a manner which obstructs the exercise of jurisdiction by local police.

Furthermore, this judgment may suggest that there is an upper time-limit for the conclusion of proceedings under Section 174, till the time someone else files an FIR in respect of the offences leading to the unnatural death. Reading such a limit into the law would be improper since it would encourage a “race to file FIRs” amongst various Police departments. It would also hamper the credibility of Section 174/175 inquiries by constraining the police to hurriedly wrap up proceedings and putting truth and justice at stake.

The Bench also considered whether Section 406 empowers the SC to transfer the power of investigation since its language presently covers only cases and appeals transferable between Courts. The Court answered this question in the negative, relying on Ram Chander Singh Sagar v State of Tamil Nadu. Considering that the original petition relied on Section 406 and prayed merely for the transfer of investigation conducted by the Bihar Police, it may also be argued that the Bench’s exercise of powers under Article 142 may be ultra vires.

This is because the Supreme Court (Amendment) Rules, 2019, award a Single-Judge Bench with the jurisdiction to adjudicate upon Section 406 transfers, while the Bench, in this case, itself held that the petition is not covered within Section 406. Furthermore, the judgment was concerned more with the DSPE Act and other provisions of the CrPC than Section 406 itself.

While the petitioner and other respondent(s) may file a review petition, only time would tell whether they would exercise such an option, in light of the sensational nature of the case and the public sentiment, something weighed in by the Court in its judgment.

The learned Judge’s ruling has upheld some well-established principles in the jurisprudence on transfer of investigation to the CBI. While it is based on original jurisdiction correctly, some portions of this judgment (while not erroneous prima facie) may have far-reaching consequences in the near future. The effect of such consequences must be mitigated in order to ensure a healthy interplay between the Constitution and criminal procedure law.

[ The author is a 3rd Year B.A. LL.B. (Hons) student at National Law University, Delhi.]